DATA CENTERS, PART-1

DATA CENTERS, PART-1Understanding Tier Classifications

When mission-critical applications fail, so can its owner. Every measure should be taken to try to prevent this from happening. Protecting the technology that run the applications is one of the first things that must be done. This task is made much easier when the technology is housed together. Housing them in a secure environment is the function of a data center. Servers, storage devices, networking gear, and the people who keep them running operate out of these facilities.

A data center, to sum it up, is the physical home of the IT capabilities of organizations.

BACKGROUND

The Uptime Institute, an independent association, developed the tier classification of data centers. There are four tiers. Tier-1 refers to a basic facility and Tier-4, to the most reliable and sophisticated type. Institute certification is recognized as the industry standard. Anyone can claim Tier-4 status but unless it came from The Uptime Institute, it should be viewed with skepticism.

The institute grants a data center its tier classification only after a rigorous evaluation of the facility’s design and sustainability. That the institute is a third-party and is the body that developed the standards give its determination a credibility that self-proclaimed claims just don’t have. Institute certification provides an objective basis for judging the capabilities of a data center.

In my experience, this is important. Between 2001 and 2003, I helped clients colocate at a large local data center that advertised its Tier-1 classification.

This was the former Exodus data center in Elk Grove Village, Illinois. Exodus went bankrupt in Q3 of 2001. Cable & Wireless USA bought it in Q1 of 2002. C&W, in turn, also went bankrupt and sold it to Savvis in Q1 of 2004. Savvis, to my knowledge, still owns it.

OVERVIEW OF TIERs

The institute’s summary of the high-level characteristics of each tier is presented below.

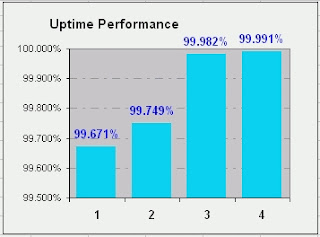

Tier-1

- Has a single path for power and cooling distribution

- Has redundant components

- And has a mean uptime availability of 99.671% (equivalent to 29 hours of downtime a year)

Tier-2

- Has a single path for power and cooling distribution

- Has redundant components

- And has a mean uptime availability of 99.749% (equivalent to 22 hours of downtime a year)

- Has multiple paths for power and cooling distribution but only path is active at any given time

- Has redundant components that make it concurrently maintainable

- And has a mean uptime availability of 99.982% (equivalent to 1.6 hours of downtime a year)

- Has multiple paths for power and cooling distribution that are all always active at any given time

- Has redundant components that make it fault-tolerant and concurrently maintainable

- And has a mean uptime availability of 99.991% (equivalent to about 13 minutes of downtime a year)

Note how small the improvement in uptime increases from Tier-1 to Tier-4. Meanwhile, the investment required to become Tier-4 is many times greater than Tier-1. In short, moving from 99.671% to 99.991% costs a disproportionate amount of dollars. Is it worth it? That’s the question for many data centers: is it? And I suppose the answer depends upon the customers that’ll use it.

Note how small the improvement in uptime increases from Tier-1 to Tier-4. Meanwhile, the investment required to become Tier-4 is many times greater than Tier-1. In short, moving from 99.671% to 99.991% costs a disproportionate amount of dollars. Is it worth it? That’s the question for many data centers: is it? And I suppose the answer depends upon the customers that’ll use it.DEFINITIONS

- Concurrent maintainability refers to the capability of being able to perform all scheduled work without adversely impacting the end-user.

- Fault-tolerance is the capability to sustain a worst case, unplanned event without adversely impacting uptime. Two major requirements for achieving fault-tolerance are redundant equipment and multiple active paths.

- Single points-of-failure refers to the location or equipment that will bring the entire system down (downtime) if that location or equipment fails. Tier-1 and –2 have many single points-of-failure. Tier-3 has several. And Tier-4 is supposed to have none.

- Site Infrastructure refers to the data center taken as a whole. A typical data center has at least 20 major mechanical, electrical, fire protection, security, HVAC, and other systems.

- Sustainability refers to the ease, convenience, and cost of operating the Data Center. A well-designed site will cost less to operate and be easier to maintain. As a group, sustainability factors account for 70% of all infrastructure failures. Human decisions and activities primarily account for sustainability factors. Two-thirds of all failures result from management errors. The remainder arise from errors made by operations staff.

- Useable capacity refers to the maximum load that the center’s systems can support. This is less than the non-redundant capacity since allowance must be made for aging components, installation errors, and the size of the desired buffer to accommodate surges in demand. Tier-3 and -4 sites are typically the ones that limit their total load to 90% of the aggregate capacity

This precedes two posts about the general attributes of Tiers. Click here to read Part-2 and here to read Part-3. A new tab or window will open for each post.

This also precedes a post about the business factors that should be considered in selecting a Tier. Click here to read it. A new tab or window will open.